Thinking about “What’s in the Box?” has helped me focus a little on my other historical research.

When I first got the box, I was working on a large-scale history project. In fact, it might have been too large to do justice to the topic. It came from a place of wanting to learn about and share a story about how farm women in the United States lived and worked on their farms in the early to mid-twentieth century, rooted in my grief over the loss of my own grandmother just before I started my doctoral program and a parallel life-long interest in Laura Ingalls Wilder, who was writing for and about farm women at the time.

As with many questions that tackle aspects of women’s history, the first step had to be looking for their voices and stories. Several options could be employed. The first, which I used, is asking people for their own stories, informally networking to see if there was some written record that could be used to uncover the past. The biggest challenge in uncovering stories of the largely voiceless is that lack of voice; once many people have passed on, there’s no record they’ve even been a part of the past.

As a journalist, I loved to tell people’s stories. I learned in my teens that everyday stories had just as much impact and interest as the big news of the day, through work in state journalism workshops and camps. One of my first features that got significant attention told the story of a cleaning woman, Lorraine, in the dorm in which I was staying for camp. It ignited for me a passion to tell the stories that remained untold. And as a journalist before I became a historian-in-training, I thought to look first toward newspaper stories to see if I could find farm women’s voices from the period I was interested in, which started in 1911.

So my first project, in a classroom under the direction of Dr. Hazel Dicken-Garcia, was a paper that examined discourse about farm women in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. As a starting point, I used the first known publication date of Wilder’s column in the Missouri Ruralist, so that I had a known date when at least one farm woman was actively writing and engaged in the farming community. As an end point, I used the last known publication date for Wilder’s column, in 1926. That left fifteen years of Press coverage to comb through, so I decided to be methodical about it. I reviewed papers from harvest and planting seasons over that fifteen years, looking for farm women’s voices. I went through everything for that fifteen years.

And found exactly one item that directly mentioned farm women.

One.

In fifteen years.

I learned several things: One, that farm women truly were going voiceless in the mainstream media during this period. For some reason, this surprised me then, but with time, experience, and further research, I’m no longer surprised by this result. Two, that the Minnesota State Fair then, as now, recognized the role of farm women in the rural communities as being significant; the item that was reported came from its grounds, where new “rest room” facilities had been built on Machinery Hill for women to use. And three, that the lack of coverage in mainstream media didn’t mean farm women were totally voiceless; the item also interviewed the female editor of a magazine called The Farmer’s Wife.

In the absence of mainstream coverage, alternate and dissident press will appear, as this one did.

The Farmer’s Wife, I discovered, was a magazine published for many years in St. Paul. It is archived at the Magrath Library on the St. Paul Campus of the University of Minnesota.

The seeds of my dissertation are planted there.

Because of the lack of coverage, I realized I needed to discover the larger story of American farm women first. While some research had been conducted at this point, no one had looked at farming magazines at the scale I decided to try. I ended up looking at six different magazines–three farming, three national mainstream press–over fifty years that marked the shift in the United States from being mostly rural to being mostly urban: 1910 to 1960. Later, I sought out other means of finding these voices, including interviews and correspondence with women who lived and worked on farms during this period. It’s during this phase of the research, which was conducted to add to the dissertation for the book that was published in 2009, that I encountered the box.

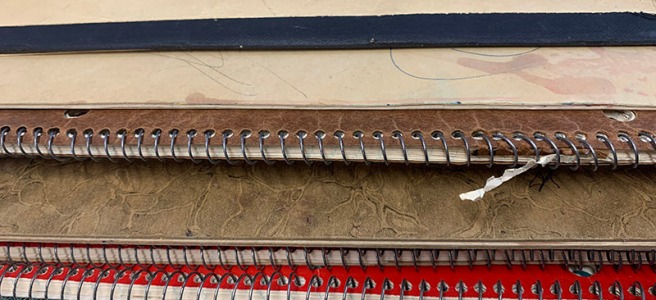

On its face, I couldn’t use the materials within it for the research I was conducting at that time. The notebooks, at a glance, were fascinating, but ultimately beyond the period I was researching. I set it aside.

Now, looking at it again, I realize the box calls for a different style of storytelling. It’s not material that would lend itself to a large-scale project. It’s more in line with a biography–a piece of history that illuminates one person’s life that in some way tells a larger story about that person’s role in history. It calls to mind Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, A Midwife’s Tale, which started with a similar diary chronicle to tease out a rich biography of Martha Ballard, a colonial midwife who lived in Maine and kept her diary from 1785 to 1812. (It won a Pulitzer Prize; it’s a brilliant book that I highly recommend.)

I don’t know what I’m going to do with those diaries yet. It’s a different sort of story, a different era from what I’m used to working in. And yet it’s very, very familiar.

One thought on “To tell a story: Ways of approaching history”